The interplay of MMA and mental illness.

A whistle-stop tour of mental illness in MMA

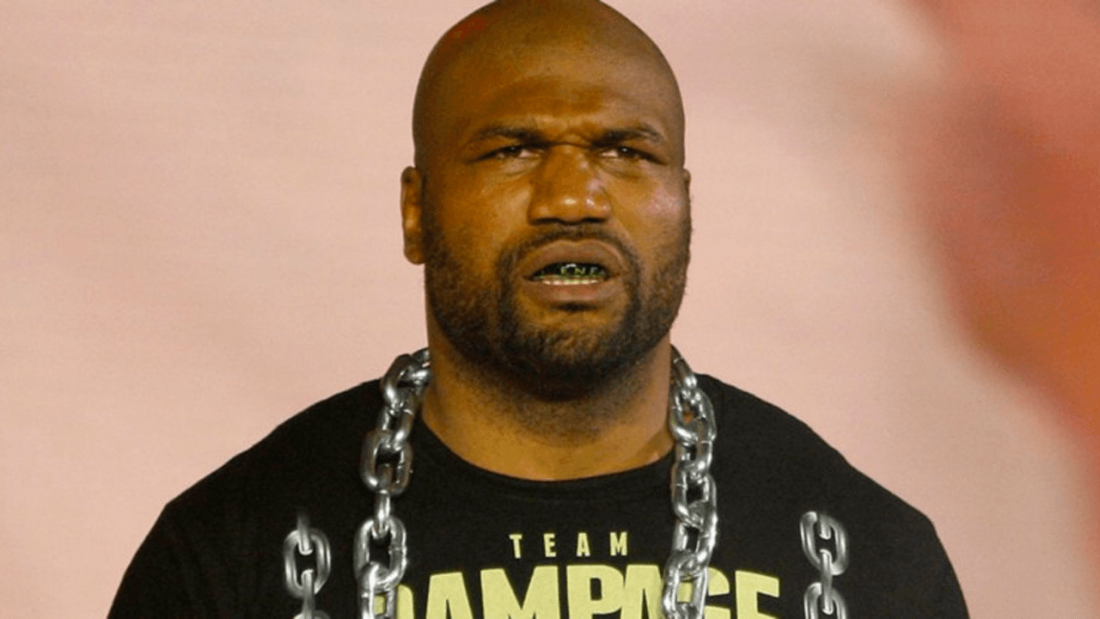

On a Californian afternoon in July 2008, Quinton Jackson, known to the world as recently relieved UFC champion ‘Rampage’ Jackson, drives his pickup truck into two cars on the freeway before fleeing the scene.

Jackson’s vehicle is wrapped in camo and adorned with huge pictures of the man himself, shirtless, wearing a steel bike chain around this neck.

When police catch up with Rampage, he engages them in a reckless high-speed chase; driving over traffic dividers before hitting several more cars. He eventually grinds to halt and police surround his car with guns drawn. The next day, Jackson is released on $25,000 bail, posted by Dana White.

The next day, at around 4:30 pm, Rampage’s friends flagged down a patrolling police car out of worry for his behaviour. Police take Jackson to a psychiatric hospital where he is held for 72 hours. He is diagnosed with delirium as the result of dehydration — he hadn’t eaten or slept in four days.

When asked by a journalist why he hadn’t eaten or drank anything in that time, he replied that it was because he had been touched by God. When asked if he’d ever suffered from depression, Jackson answered…

“No. I’m not depressed. Do I seem depressed?…I’m happy — you see why I drive around laughing at stuff all the time? Do I look like a depressed person?”.

In 2014, welterweight champion Georges St. Pierre retired from fighting at the height of his reign. He revealed to have suffered from OCD since childhood, with the pressures of fighting overwhelming him. As welterweight king, St. Pierre claimed he could never relax. Even on vacation, he would fixate on the next opponent and potential strategies.

In 2016, after suffering a head-kick KO and losing her title, Ronda Rousey broke down in tears on the Ellen Show. She admitted that straight after the fight she asked herself, “what am I if I’m not this?” and considered committing suicide…

“In that exact second, I’m like, ‘I’m nothing. What do I do anymore? No one gives a shit about me anymore without this.’”

Earlier this year, the wife of former UFC interim lightweight champion Tony ‘El Cucuy’ Ferguson the police. Ferguson had thrown ‘holy water’ on her, expressing paranoid delusions about people being inside the walls and complaining that a computer chip had been implanted in his leg. His wife assured police that Ferguson hadn’t been violent, just that his behaviour was erratic and troubling, and that he was refusing to accept help.

Recent reports are reassuring. Ferguson posted on twitter yesterday: “Psychologist appt went well, thanks doc”.

Is there a causal link here?

Prize-fighting is a perfect storm of mental illness.

Fighters often come from difficult backgrounds. Rampage Jackson recalled being taken under the wing of a drug dealer at 8 years old. Recently dethroned UFC strawweight ‘Thug’ Rose Namaunas has discussed suffering sexual abuse and witnessing violence growing up. Thug Rose’ father, who suffered from schizophrenia, sadly died when she was 16.

The octagon itself brings unpredictable emotional ups and downs. There are considerable financial incentives to winning (sometimes doubling the paycheck), and the feeling of failure after a loss can be unbearable. Several other MMA fighters have detailed their experience of depression after a loss or even in periods of injury.

There’s also the issue of traumatic brain injury, shown to happen more often in MMA than boxing (likely because of the standing 10 count and referees checking fighters after a knockdown). Traumatic brain injuries are defined by memory loss, poor impulse control as well as anger and depression. Studies show that mental symptoms can manifest decades after physical injury.

Although cage-fighting can exacerbate poor mental health, martial arts training has proven to be uniquely effective for the treatment of depression, PTSD, anxiety, and drug addiction. More on that next time.

Thanks for reading.